So you’ve decided to destroy your fictional civilization and for reasons of verisimilitude, you want to draw on a historical model. Your first thought may be to rotoscope the collapse of the Western Roman Empire … and why not? It worked so well for Isaac Asimov. The problem is it worked for a lot of other authors, too—the Fall of Rome is well-chewed gristle at this juncture. Perhaps other models would make a nice change?

Granted, other models may not be as well known as the Roman one, at least to Western readers. Generations of Westerners learned Latin and read Roman history; generations read Gibbon’s Decline and Fall.

Plus, other collapses were, no doubt, so thorough that we have no inkling they even happened.

Still, there are some collapses and calamities about which we have some knowledge. I have a few suggestions.

Boom, Baby, Boom

Large eruptions like Toba 70,000 years ago or the Yellowstone eruption 640,000 years ago are very sexy: one big boom and half a continent is covered by ash. But why settle for such a brief, small-scale affair? Flood basalt events can last for a million years, each year as bad as or worse than the 18th century Laki eruption that killed a quarter of the human population in Iceland. Flood basalts resurface continental-sized regions to a depth of a kilometer, so it’s not that surprising that about half the flood basalts we know of are associated with extinction events. In terms of the effect on the world, it’s not unreasonable to compare it to a nuclear war. A nuclear war that lasts one million years.

N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth series gives some idea what a world in the midst of the formation of a Large Igneous Province might be like. In Jemisin’s world, there are people who can at least moderate the effects of an eruption. In ours, of course, there are not. As horrific as the Broken Earth is, the reality of a flood basalt event would be much, much worse. And that’s leaving aside resurfacing events on the scale of Venusian eruptions.

Holocene Big Melt

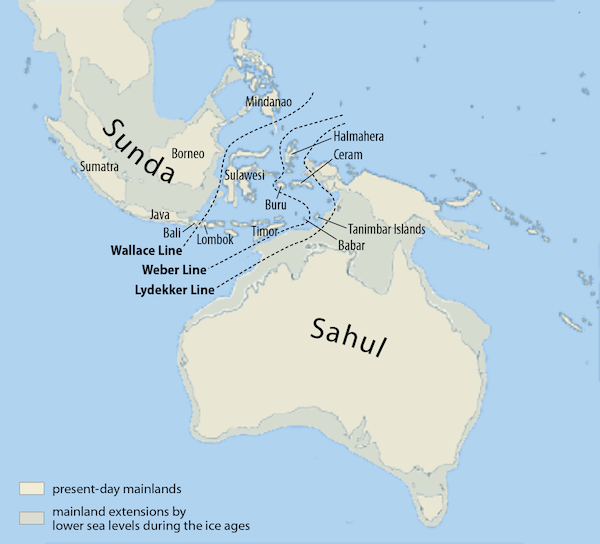

The transition from glacial to interglacial predates the oldest known cities, but if there had been towns comparable to Uruk or Jericho 12,000 years ago, we might not necessarily know about it. We do, however, have some idea how the world changed when it warmed. Humans love to settle along rivers and seashores and the latter are radically altered when ice sheets turn to liquid water. Take, for example, Sundaland:

When sea levels were lower, Sundaland’s land area was close to twice as extensive as it is now. If humans built villages along the coastline twelve millennia ago, any relics would now be under many meters of sea water. Humans have occupied the region for a very long time, but our understanding of what the coastal cultures were doing during the glacial periods may be hobbled by the fact that a lot of the evidence is currently inaccessible.

We live in an interglacial period. Many of the ice-sheets that fed sea level rise are long gone. The good news for writers is the ice sheets that are left are still more than adequate for some serious coastal restructuring. Add in the disruptive effects on agriculture and a post-Big Melt world could be a much emptier1 , unfamiliar-looking world. Consider, for example, George Turner’s (probably more obscure than I realize) classic Drowning Towers.

Bronze Age Collapse

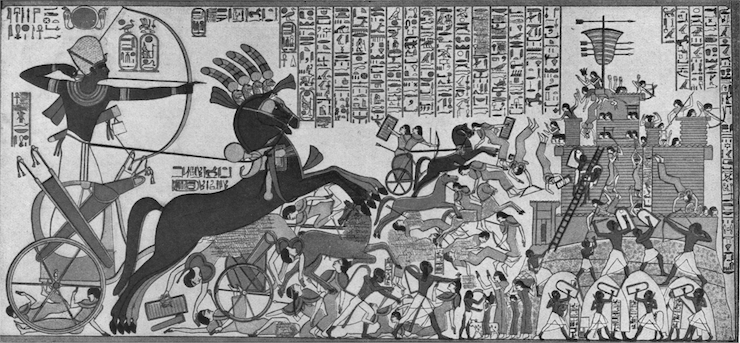

In the 12th century BC, cities all around the Eastern Mediterranean were burned, trade routes collapsed, large states declined, and some vanished entirely. It took centuries for civilization to recover. The powers that rose were in many cases new nations, speaking languages that would have been unfamiliar to people living in those regions a few centuries before. Whatever happened to the Bronze Age cultures of the Mediterranean seems to have been devastating.

One problem with incredibly devastating events is record-keeping becomes much harder when one’s city is being burned. Even when records were kept, the languages they were written in were replaced. As a result, what seems to have been an End-Permian catastrophe to the Fall of Rome’s K/T is more obscure than it really should be, and the possible causes more of a matter of disputed conjecture than one might expect. Our friend climate change appears, of course (because cultures dependent on predicable weather for agriculture react badly to sudden climate changes2 ), among a myriad of other possibilities.

One of my favourite hypotheses is disruptive technological change: cheap iron replacing expensive bronze had as a side effect the overturning of a complex social order, and thus the sudden collapse of everything dependent on that social order. It would be extremely comic if all it took to duplicate one of the most dramatic setbacks human civilization has suffered was something as simple as global computer networks. Or Twitter.

Trade Decline

Lunar colonists might look to Petra as an example of what can be achieved in a hostile, demanding environment. Surrounded by desert, the people of the Nabataean capital were remarkably adept at harnessing the resources they did have. In fact, they not only survived, they prospered, thanks to their strategic location in a Mediterranean-Middle Eastern trading network. At least, they prospered until the city declined and fell into ruin.

It is believed that the city fell to several earthquakes (which destroyed a sophisticated water storage and management system) and also declined due to a shift in trade routes. The Arab conquest may have completed the catastrophe.

Petra could be a model for the decline and fall of nations unaware that their trading partners have alternatives, or more SFnally, space colonies. Natural disasters and shifts in trade routes can befall whole planets. A minor subplot in Clarke’s Imperial Earth touches on this: what of Titan’s hydrogen export-based economy when demand for reaction mass falls dramatically?

New World Expansion

Fifteenth-century Europeans were the equivalent of plague rats; they carried with them a millennia-long heritage of contagious diseases. They were descended from the survivors of the epidemics and pandemics, which means they enjoyed a degree of resistance to the diseases they carried. The unfortunates of the New World had no resistance. Their populations declined 90% or more over the next centuries. Small wonder that people struggling to survive in a post-apocalyptic hellscape were unable to prevent waves of infectious, violent invaders from stealing their land.

SFnal diseases tend to be far more lethal than the historical ones, probably because killing 999 in 1000 is more dramatic than 9 in 10. Ninety percent lethal virgin-field infections are still more than sufficient to kick the legs out from under heretofore successful civilizations, to leave the survivors unable to maintain their records and infrastructure, and unable to deal with other challenges that might arise (like the arrival of land-hungry, genocidal strangers). How precisely this might come about NOW might be a challenge to imagine, given modern medicine. I suppose one could imagine people suddenly deciding en masse to abandon proven technology like vaccines, but that seems pretty far-fetched…

While most authors opt for virgin field epidemics that kill all but one in a thousand or one in a million, there is at least one exception: Algis Budrys’ Some Will Not Die begins in the aftermath of a plague that has eliminated 90 percent of the population.

Natural disaster, technological missteps, epic cultural mishaps…it’s all good for the author who needs to sweep away the old to make room for the new. Or perhaps, if the mishap is large enough, for those who long for the tranquil quiet of an empty world.

1: I see some worried faces out there. Take comfort in the fact that the rich may have the resources to survive the calamity their own profit-seeking behaviour will cause. Even better, they can arrange for such history books as are written to lay the blame on the plebs who have been swept away by the demise of the old order.

2: Again, no need to worry that this will needlessly inconvenience our oligarchs. Even if agriculture shuts down for a few decades, the unnecessary masses can be converted into a nutritious slurry to keep their betters fed.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

[1]I see some worried faces out there. Take comfort in the fact that the rich may have the resources to survive the calamity their own profit-seeking behaviour will cause. Even better, they can arrange for such history books as are written to lay the blame on the plebs who have been swept away by the demise of the old order.

[2]Again, no need to worry that this will needlessly inconvenience our oligarchs. Even if agriculture shuts down for a few decades, the unnecessary masses can be converted into a nutritious slurry to keep their betters fed.